What to know about the electoral college

/American citizens have some crazy notions about the Electoral College. Here are a few key truths that everyone should know. The purpose here is not to take one side of the argument and insist that it (and only it) is correct. Rather, the intention here is to set aside five really bad reasons for taking one side or the other.

The Founders Did Not Design It This Way

The Electoral College process that exists today is not what the founders envisioned. A reasonable person can support the College, but no one should defend it by claiming the wisdom of the founders.

The founders intended the president to be chosen by small ad hoc committees of trusted local men in each state. They intended citizens to vote for their electors and trust them to use their good judgment to pick a president from among the nation’s most prominent leaders. They intended those electors to convene in their respective states and choose men based only on character and public service, with no campaigning by candidates. As explained in Federalist #68:

[T]he people of each State shall choose a number of persons as electors . . . who shall assemble within the State, and vote for some fit person as President. Their votes, thus given, are to be transmitted to the seat of the national government, and the person who may happen to have a majority of the whole number of votes will be the President.

Alexander Hamilton, who wrote #68, promised that if presidents were chosen by this method, America would be guaranteed excellent leaders:

The process of election affords a moral certainty, that the office of President will never fall to the lot of any man who is not in an eminent degree endowed with the requisite qualifications. Talents for low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity, may alone suffice to elevate a man to the first honors in a single State; but it will require other talents, and a different kind of merit, to establish him in the esteem and confidence of the whole Union. . . It will not be too strong to say, that there will be a constant probability of seeing the station filled by characters pre-eminent for ability and virtue.

Clearly, the system we have today is a perversion of the founder’s design. Here are four very strong contrasts between the founders’ design and the modern practice.

The founders intended citizens to vote for electors they knew and trusted. Today, voters seldom know the name of their electors.

They intended electors to have real decision-making power. Our electors are expected (and in some states legally required) to automatically cast their votes for the top vote-getter in the state’s popular vote.

They intended candidates to wait quietly to be called. Our candidates run aggressively. What Hamilton dismisses as “the little arts of popularity,” which in our time include fundraising, sloganeering, and looking good on camera, are the main features of modern presidential campaigning.

They intended each state to support at least two candidates. The winner-take-all method used in 48 states throws all the states’ electoral votes for one candidate — even when the voting in a state is closely divided.

The Electoral College Doesn’t Protect Small States

It is not wrong to want to protect small states’ interests. All fair-minded citizens, including those who live in large states but want fairness for all, can support provisions that ensure small states are not mistreated.

The founders recognized the necessity of protecting small-population states. And they established the needed safeguard in the Congress — particularly in the US senate, where each state has the same number of senators. The 25 smallest states have a combined population (in 2020) of 58 million, which is less than 18% of the nation’s population. But that contingent accounts for 50% of the votes in the US senate. So, a faction of the smallest states can easily thwart the majority based only on the power given them in the senate. To the extent that government action requires senate concurrence, the small states are protected.

There are those who say that a similar small-state lever is needed in the executive branch, too. But the executive branch is not designed to represent, but to execute the laws. To demand that the office of the president provide representation for the diverse interests of national sections and factions, ignoring that the president has other duties and the congress exists to provide representation, is like demanding that the local public library provide firefighting services as well as books. It’s silly. The fire department already has fire trucks and is already trained to fight fires. The library ought to be left to focus on books.

New York and California Do Not Dominate National Politics

Among supporters of the Electoral College are a subset of people who assert that New York and California pose an immediate existential threat to the rest of the country. Here’s a clip of such an opinion gleaned from the social media site Quora:

Note that New York and California are both described by the commenter as “huge.” New York city is described as “especially “ huge. The commenter asserts that NYC, by itself, contains “nearly as many folks . . . as the whole state of Ohio.” It is true that NYC (8.5 million) has nearly as many people as Ohio (11.8 million). But David Phillips doesn’t explain why that demands consideration.

In point of fact, California is the most populous state, but it has less than 12% of the US total. New York represents just over 6% of the US population. The combination of those two states could not dominate American politics on the strength of their 18% share. New York and California together have four US senators, which is 4% of the total. California and New York have 55 and 29 electoral votes, which is 15.6% of the total. In terms of popular votes (in the 2020 presidential election), the two states’ citizens cast just over 26 million votes, which was 16.5% of the nationwide total.

So the argument that the electoral college provides an effective shield against New York and California depends on believing that 16.5% of the popular vote would make them an irresistible juggernaut, but that 15.6% is a portion that keeps them in their place.

Setting aside the fear of just two states, we can ask, “How many of the largest states are needed to capture a majority?” And the answer (based on 2020 population) is the nine largest states. Those states are California, Texas, Florida, New York, Pennsylvania, Illinois, Ohio, Georgia, and North Carolina.

But those nine states are not an anti-small state bloc. They have nothing in common except they all sit at the top of the nation’s population ranking. They are found in the East, Midwest, South and West. Five of the nine went for Biden in 2020 and four went for Trump. There isn’t any large-state faction in the 21st century that small states need to guard against.

The electoral college hardly changes the balance, either. Those aforementioned nine largest-population states account for 50% of the population but 44.6% of the electoral votes. We need to add two additional next-largest states (Michigan and New Jersey) to make a gang of 11 states that has more than 50% of the electoral vote.

The people who support the electoral college because they think it shifts the balance away from a too-powerful large-state cabal are wrong about everything. First, there isn’t any large-state cabal. And second, the electoral college makes only a tiny difference in the proportion of power each state has.

There is No Conflict Between the Coasts and the Heartland

Supporters of the electoral college typically cast the conflict as New York and California versus the heartland. But I’ve shown above that New York and California account for only 18% of the nation’s population and could not dominate anything based on population or popular votes. When that is pointed out, EC supporters like David Phillips sometimes expand their phrasing to encompass “the liberal coasts versus the heartland.”

But that framing is flawed, too. If the nation is sorted into four regions (East, South, Midwest and West) the electoral college shifts weight within the regions as much as it does between the regions. The electoral college punishes states in every region if they are large, and punishes conservative states as wall as liberal states if they are large.

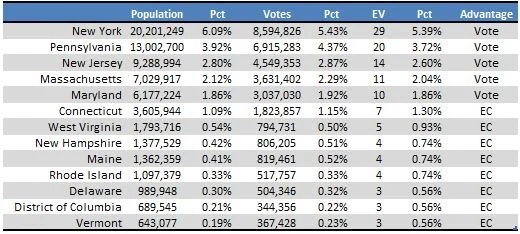

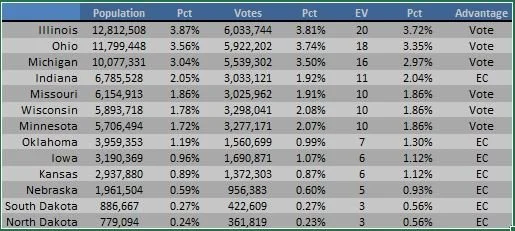

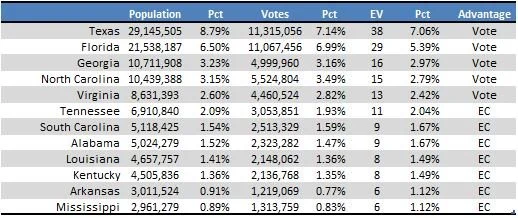

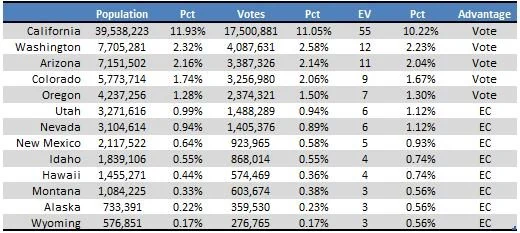

The following four tables summarize data from 2020, including each state’s population, its number of popular votes cast, and its share of electoral college votes. By comparing the Pct values next to each value we can see how much the electoral college alters the state’s share. For instance, New York has 6.09% of the nation’s population. In the 2020 presidential election, New York voters cast 5.43% of the popular votes cast, and 5.39% of electoral college votes.

Eastern States Population, Electoral & Popular Votes

Midwestern States Population, Electoral & Popular Votes

Southern States Population, Electoral & Popular Votes

Western States Population, Electoral & Popular Votes

The farthest-right column in each table shows whether the states has an advantage in popular vote or electoral college. There are winners and losers in each region. With one exception, the five or six largest states in each region would have to greatest influence under a popular vote, and the rest of the states in each region would gain more influence with the electoral college. The exception is Indiana in the Midwest, which loses its popular vote advantage due to low voter turnout in 2020.

These tables show that the electoral college does not confer a benefit to heartland states at the expense of the coastal states. Illinois, Ohio and Michigan are heartland states that lose share due to the electoral college.

The Electoral College Doesn’t Broaden Presidential Campaigning

Another argument about the electoral college that holds no water is that with popular voting candidates for the presidency would only campaign in the big states and would pay no attention to the smaller states. The opposite is true. The campaigners would know that no state can be take for granted. Now, the democrat candidate takes California’s 55 electoral votes for granted and spends less time there than they might if every vote added to their popular vote total.

NB: After reapportionment in 2022, California’s electoral vote reduced to 54.