Do Constitutions Matter?

/Some people believe that America owes its greatness to our excellent Constitution. This requires believing several things. First, that American is great; second, that our Constitution is excellent; and third, that constitutions matter. It requires believing that the US, and other countries, are shaped, for good or ill, by their constitution. This essay touches only on that third idea.

Scholarly research finds only a weak connection between quality of life in countries and the provisions in their national constitutions. Professors David S. Law and Mila Versteeg published the article in the California Law Review in 2013.

Versteeg and Law identified 15 rights that are often mentioned in national constitutions. They chose to investigate only rights that could be observed so they could reliably determine if the people of a country have the right or not. Here are the 15 rights:

Prohibition of torture

Economic equality for women

Social equality for women

Right to a fair trial

Minority rights

Freedom of expression

Right to education

Right to vote

Freedom of assembly

Habeas Corpus

Right to health

Religious freedom

Protection from arbitrary arrest

Freedom of movement

Prohibition of Death Penalty

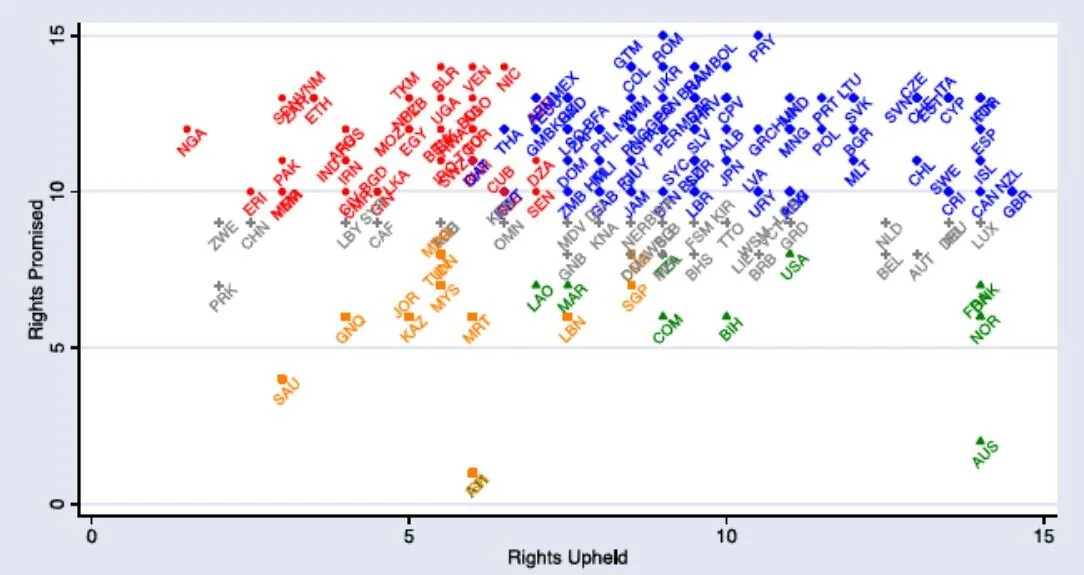

The study catalogues 167 countries and their constitutions. Other countries were left out if the investigators could not get reliable up-to-date information about economic and social conditions there. Of those 167 countries, 44% were classified as having “Strong” constitution — meaning constitutions that promise a lot of protections and seriously deliver on those promises. These are blue in the table. Twenty-three percent are Sham (red) constitutions. Those promise a lot, but don’t deliver. Weak constitutions (promise little and deliver little) are 8% of the sample (orange). Modest constitutions are green in the table and represent 7% of the total. Modest constitutions don’t promise much, but people in those countries have good lives nevertheless. The US constitution is classified in the study as a modest one. Finally, about 18% of countries cluster at the center of the table and don’t fit any of the four categories.

The study is an international comparisons and doesn’t focus on the US. But Versteeg and Law recognize the US as an “over-performer” — a country that delivers more than it promises:

[T]he countries that populate the upper echelons of constitutional over-performance combine relatively stingy constitutions with strong human rights practices. A number of these countries have relatively old constitutions, which is entirely consistent with our earlier finding that older constitutions tend to contain a less comprehensive assortment of rights. The United States and Norway, which consistently rank in the top ten, possess the world’s oldest and second-oldest constitutions, respectively.

Life in America is pretty good. America compares favorably to many other countries because American people are mostly decent and well-behaved. Our country measures positively on 12 of the 15 types of social and economic rights. But the Constitution is not the source of all those rights and privileges. Only four of the social and economic benefits listed in the study are mentioned in the Constitution. Americans don’t get tortured, for example. But America’s Constitution doesn’t prohibit torture of American citizens. It doesn’t say anything about torture at all. And it is not reasonable to suppose that the Constitution does more than it explicitly intends to.

In the conclusion of the report, Versteeg and Law issue a challenge to experts like themselves — but also to ordinary citizens — not to expect too much results from any constitution:

[C]onstitutional scholars and lawyers are heavily invested in the notion that formal constitutions are important as a practical matter. It is difficult to rationalize the inexhaustible production of scholarship on constitutional interpretation if one takes the position that constitutions are inconsequential.

Few constitutional scholars would spurn the opportunity to participate in the drafting of an actual constitution on the ground that their time would be better spent doing something more useful. On the other hand, there is a long tradition of skepticism about the efficacy of so-called parchment barriers. “Every banana republic,” as Justice Scalia has wearily observed, “has a bill of rights.”

The Constitution specifically ensures that a few rights and privileges won’t be curtailed by Congress. But for the rest, we have to thank each other.

Discuss:

Does it surprise you that the US Constitution guarantees fewer right to American citizens than many other constitution give to their citizens?

What additional rights do you think should be written into the Constitution?

What rights that already exist in the Constitution ought to be more effectively guaranteed?