Compared to what?

/What information is necessary to understand the 2020 coronavirus pandemic? And I means that from a narrow epistemological perspective. Setting aside the ethical, and practical, and political questions that are being treated elsewhere.

What does a person need to know? For one thing, you need some sense of how the coronavirus news fits into the normal flow of life. As of April 10, 2020, Johns Hopkins University was reporting 16,686 confirmed deaths from covid-19 in the US.

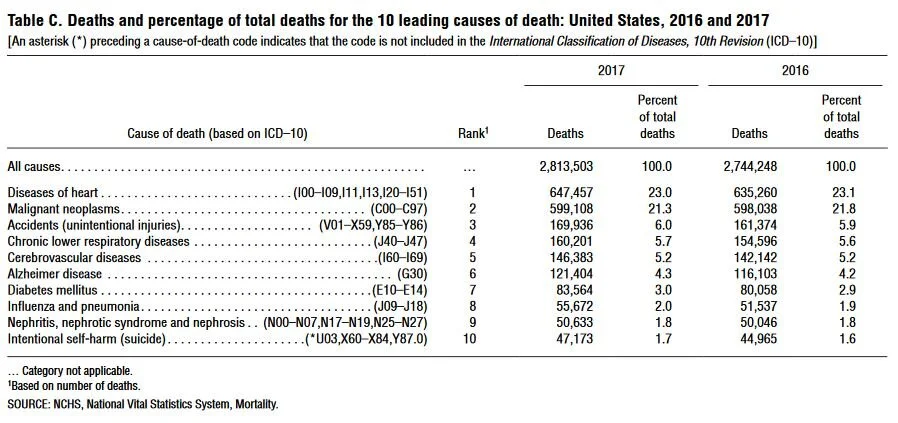

The best source for information on mortality in the US is the Center for Disease Control. And the CDC reports around 2.8 million Americans die each year. In a nation of 320-million, that amounts to 0.8% annual mortality. In other words, less than, but almost, one percent of the population dies each year. That overall death rate varies by age and region of the country and genders, and race, and income, and access to health care. But all together, the primary causes of death in America are consistent across years.

Click on the CDC link to learn details about the primary cause of death for particular age groups, variations by regions of the country, etc. The main thing to learn is that there is no place in the country, and no group of the population, for whom the death rate is zero.

Look at the chart again and find the number of deaths from respiratory disease and from influenza and pneumonia. Those two causes (which are closely related to covid-19) account for close to 220-thousand deaths each year.

At the ordinary rate of death in the US (roughly 7,800 deaths per day) across the 40-some days since the covid-19 pandemic began, you could expect around 330-thousand deaths. So, in the midst of the covid-19 emergency, when almost everything is being sacrificed to cope with this single concern, the crisis itself — at its worst — accounts for only about 5% of the deaths occurring.

If we consider only the usual number of deaths every year from respiratory disease and influenza and pneumonia alone, we would expect 600 deaths per day, or 25,000 deaths during the 40-some days of the crisis so far. That is twice as many as the number of covid-19 deaths.

If coronavirus is adding 16,686 additional deaths on top of the usual number, that is a 66% increase in mortality. That is horrifying! If, however, some or even most of the deaths attributed to covid-19 are actually people who were already ill from some respiratory disease or from flu or pneumonia, the covid-19 may just be a different way to classify deaths from respiratory disease.

I’m not saying it is one or the other. I’m saying both are possible. And I’m saying we don’t have the facts to know which it is.

In a Washington Post opinion column on April 10, 2020, journalist Fareed Zacharia considers that the scope and scale of the crisis has been build on guesses from the beginning, and that as time goes by and more data is compiled, those early guesses appear wronger and wronger.

A group of Stanford University scholars believe that the basic reason that estimates of deaths have had to be revised downward is because without widespread testing from the start, we didn’t realize how many mild or asymptomatic cases there would be. That means the denominator — those who have been infected — is larger than initial estimates and the fatality rate for covid-19 is lower. (If two out of 100 people with the virus die, the fatality rate is 2 percent; if two out of 1,000 die, it is 0.2 percent.) In March, the World Health Organization announced that 3.4 percent of people with the virus had died from it. That would be an astonishingly high fatality rate. Fauci suggested a week later that the actual rate was probably 1 percent, which would still be 10 times as high as the flu. Since then, we have learned that many people, perhaps as many as half, don’t have any symptoms. Some studies find that 75 to 80 percent of people infected could be asymptomatic. That means most people infected with the virus never get to a clinic and never get counted.

How bad covid-19 really is depends on two things: how deadly it is and how infectious it is. If it isn’t deadly — if most people who get it suffer a few days of fever and a cough and then get better — then it shouldn’t be a bid deal. Likewise, if it is not easily transmitted from one person another then it will will fade out on its own.

America’s, and the world’s, response to covid-19 has assumed the disease is both highly contagious and very deadly. As Zacharia explains, those assumptions were initially just guesses. They were the guesses of experts, but even experts aren’t very good at predicting when they don’t have accurate and detailed data. In the case of covid-19, three numbers are necessary to make accurate predictions.

people exposed to the virus

people who catch the disease

people who die of the disease

An accurate measure of how deadly covid-19 is can only be determined by computing the percentage of all people who catch the disease and then die of it. And there is now no accurate total number of people who’ve caught the disease. Especially in the US, where there has been little testing, we just don’t know who’s had it. My daughter had the symptoms. But there was no way she could get tested, and we’ll never know if she had it or not.

An accurate measure of how contagious covid-19 is can only determined by computing the percentage of all people who are exposed to the disease and then catch it. And there is nothing like an accurate count of the number of people who’ve been exposed.

Notice, please, that I am not saying anyone is inflating the numbers or minimizing the numbers or faking the numbers in any way for the sake of political gain. I believe that does happen. But that isn’t the point I am making. I’m saying that what makes an expert an expert is knowing a lot of facts. And in the case of the emerging novel coronavirus global pandemic of 2020, the people we look to for expertise simply don’t know as much as experts typically know about their subject. People like Dr. Anthony Fauci certainly know the most, and we ought to heed their advice. But we should also remember that they are guessing.

Leaders in Washington and many states have taken actions based on guesses and on ethical judgments about the right thing to do. They have chosen to cripple the economy for a time, in order to moderate the peak number of cases of the disease by an amount that cannot be calculated.